German Army butter dish variants

An item issued to most if not alls soldiers was the butterdish or Fettbuchse. These were first introduced in 1938 by the Heeres Verordnungs Blatt 203 von 1938 Teil B. Is is unclear when they were first issued to the troops exactly. The butterdish was meant to contain the daily ration of 72 grams of Fett which was butter or margarine; but it had room for up to 200 grams.

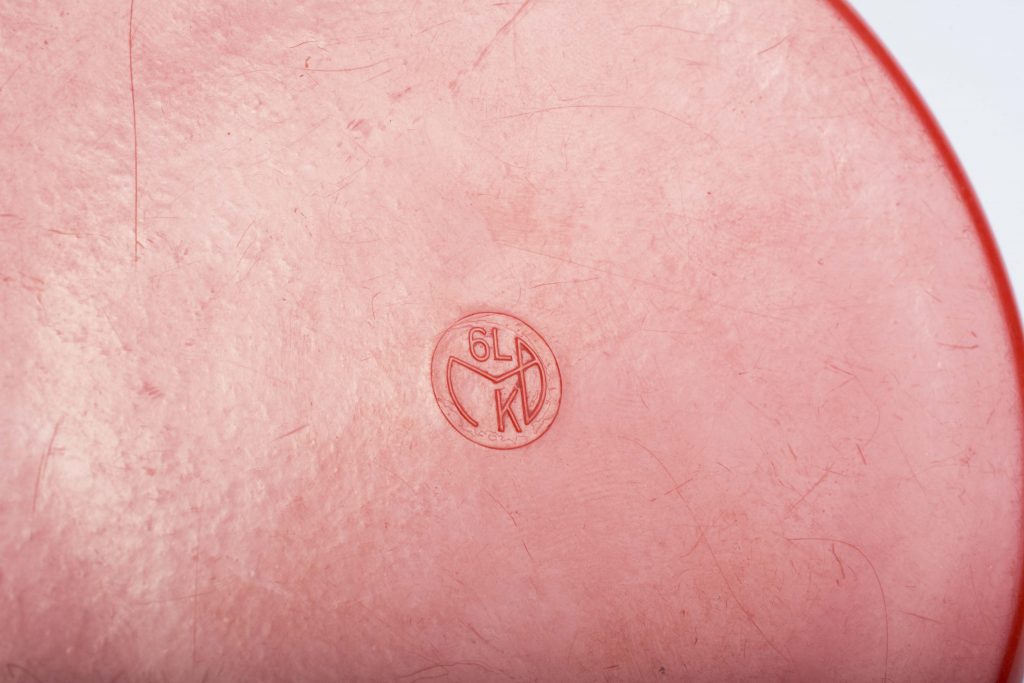

Early plastics were quite common within the Wehrmacht and they were used for many different appliances; the speed and cost of production, heat resistant and non-conductive properties proved their usefulness throughout the war. These plastic containers are almost always referred to as being made from Bakelite which is only partially true, however most are actually made from Urea resin with organic fillers. These early plastics are mostly marked with the MPAMD marking which means Material Prüfungs Amt Berlin Dahlem“. These markings can be deciphered in maker, material and filler material. The latter indicated that to reduce the cost of production; filler material was inserted during production making it less pure. Typical fillers for these early plastics were Rock (talc) Dust, Asbestos Fibers, Asbestos Cord, Sawdust, Wood Chips, Short Textile Fibers, Shredded Textile Fibers, Textile Fabric Strips, Short Fibered Paper Flakes, Paper Shreds or Layered Paper (cardboard) Strips.

It is uncommon to see date markings in butterdishes, but it did happen.

Sometimes glass inserts can be observed inside both the first and second pattern butterdishes as the civilian or private purchased variants.

These butterdishes are quite collectible as there were a huge number of colour and designs variants in production. In general, we can divide the variants into two groups. The first, and the second pattern butterdishes. The first pattern has only vertical ridges on the lid, whilst the second pattern features them on both lid and body. There is no solid proof as to which was produced first, and it may be so that production of both styles was simultaneous. The thread used on the closure can be fine or coarse, and with varying numbers of turns to open and close them. Some sources state that when a butterdish takes more than one full turn to open, it is post war; this is not completely true as we will illustrate in this article. All butterdishes pictured below are wartime unless stated otherwise. Another difference to both types is that the first pattern was made with a large variety of thread be it fine or coarse and a number of different turns required to open. The second pattern, as far as I’ve observed was only made with fine thread.

Other than the standard sized dishes; there are deeper variants which had a capacity of exactly two or three times the standard size. There is no official explanation for the size of these large butterdishes other than that it might be plausible that troops serving at the far end of the supply chain such as Gebirgsjäger carried twice the ration. This is however an assumption, albeit the most plausible explanation for the model. These are also made with the same moulds as the standard dishes and the lids are interchangeable.

Other than the standard sized dishes; there are deeper variants which had a capacity of exactly two or 4 times the standard size. There is no official explanation for the size of these large butterdishes other than that it might be plausible that troops serving at the far end of the supply chain such as Gebirgsjäger carried twice the ration. This is however an assumption, albeit the most plausible explanation for the model. These are also made with the same moulds as the standard dishes and the lids are interchangeable. All bear the same marking 1092.

Another variant is the salt shaker, which was an issue item. It is assumed that these were issued for use in tropical climates where excessive sweating caused a significant fluid and salt loss. These featured a large compartment which has a few pointy edges to break up the large salt lumps. The lid has a smaller lid which can be opened revealing several small holes to distribute the salt. There are several theories about these containers but the only plausible theory is the salt shaker theory. There are a number of Soldbuch entries of troops issued both the Fettbuchse and the Salzstreuer, attributable to units serving in tropical climates. The salt shaker is observed in Orange, speckled brown, black and white material.

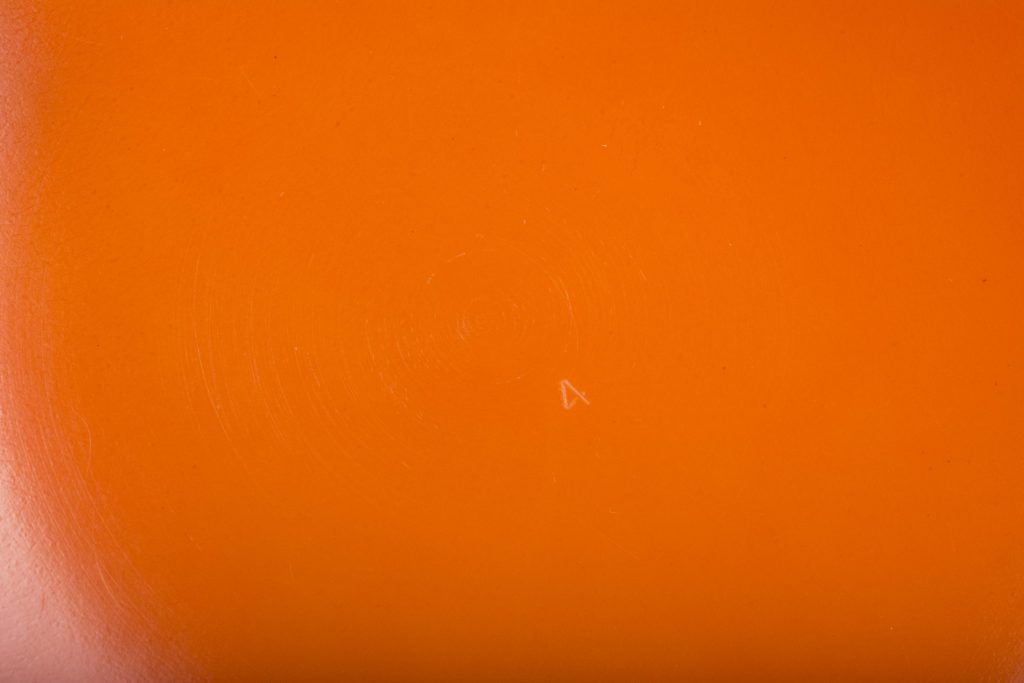

In the differentiation of different design models I will use the orange examples to illustrate to keep things simple. I will differentiate in colours in a later stadium. These examples pictured below are all wartime examples unless stated otherwise. All names and or types given are of my creation; this is not official wartime nomenclature.

Design variants

First pattern, type 1.1

Marking: 2E K

Material K: Urea resin with organic filler material

Maker: 2E

Weight: 102 gram, 210 gram with glass insert

First pattern, type 1.2 ‘Convex lid’

Marking: –

Material K: Urea resin with organic filler material

Maker: –

Weight: 88 gram

First pattern, type 1.3 ‘Rimless body’

Marking: 7N K

Material K: Urea resin with organic filler material

Maker: 7N

Weight: 84 gram

First pattern, type 1.4 ‘Fine thread’

Marking: Four point marking M4 K

Material K: Urea resin with organic filler material

Maker: M4; Kronacher Porzellanfabrik Stockhardt und Schmidt-Eckert

Weight: 107 gram

First pattern, type 1.5 ‘Flat lid’

Marking: 22K

Material K: Urea resin with organic filler material

Maker: –

Second pattern, type 2.1

Marking: AA K

Material K: Urea resin with organic filler material

Maker: AA which is a unknown maker marking

Weight: 93 gram

Second pattern, type 2.1 ‘ Convex lid’

Marking: –

Material K: Speckled brown Urea resin

Maker: –

Salt-dispenser or Salzstreuer

Material K: Urea resin with organic filler material

Maker: amh indicating production by Hans Buellman-Werke, Gablonz / Schlag, Sudetengau

Weight: 98 gram

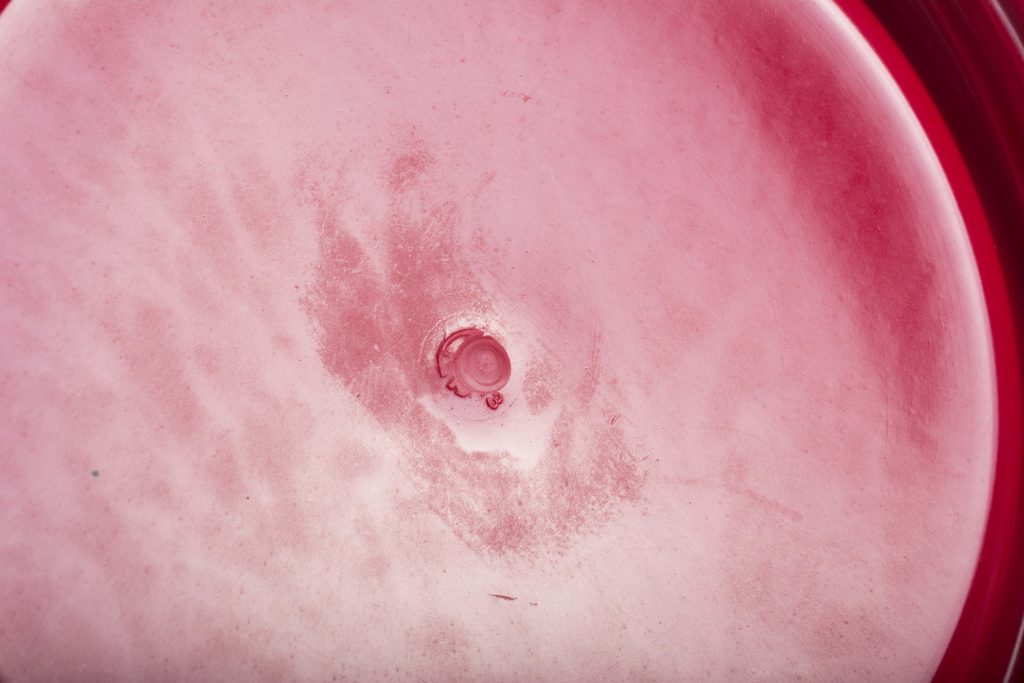

Colour variants

There are endless coloured variants ranging from the most common colour orange right down to pink, mint green to red, brown and light blue. Just like their canteen cup counterparts; it is unknown why all these varieties exist. There is no set explanation why some examples are green, whilst other are orange or black.

Post War examples

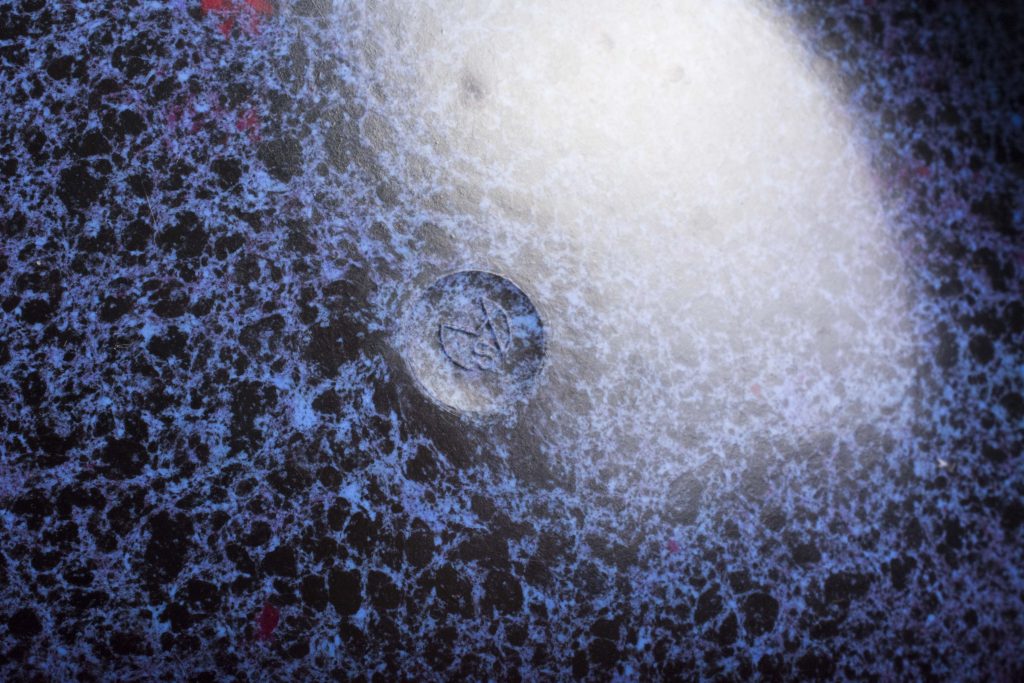

First pattern, Post war example marked BGS

Marking: BGS indicating Bundesgrenzschutz post 1951

Material: Phenolic resin with shredded textile fibers

Maker: –

Weight: 116 gram

Notes: This is the most well known post war example that is offered as being a wartime model. They are sometimes unmarked, or with erased markings. This example can be easily recognized by the marble like material and the multiple full turns needed to open it.

First pattern, Post war example marked ‘A’

Marking: The A is modeled after the Assmann logo

Material: Phenolic resin

Maker: –

Weight: –

Notes: This is a well known post war example that is offered as being a wartime model. They are sometimes unmarked, or with erased markings. The recognition point of these is that they need several turns to open!

Distinguishing original butterdishes from reproductions

There is a general feel when you are observing wartime plastic. It is heavier then most of its modern counterparts which are made from modern plastic which holds a certain amount of flexibility which early plastic’s don’t have. The wartime plastic is heavier at sometimes twice the weight of its reproduction counterpart. Whilst wartime bakelite or resin bears little to no tool marks; the modern made reproductions often bear tool marks at the edges around the thread. Wartime bakelite or resin is very hard and if you’d drop it it will probably shatter. Gently tapping bakelite or resin against a metal object or your teeth it will recreate a glass like sound whilst modern plastic sounds rather soft. There are countless tips and tricks to be tried when testing old plastics but the best way to learn is to handle loads of wartime plastics or bakelite so you’ll get the feel for it.