M38 camouflage smock – Waffen SS – Lateral

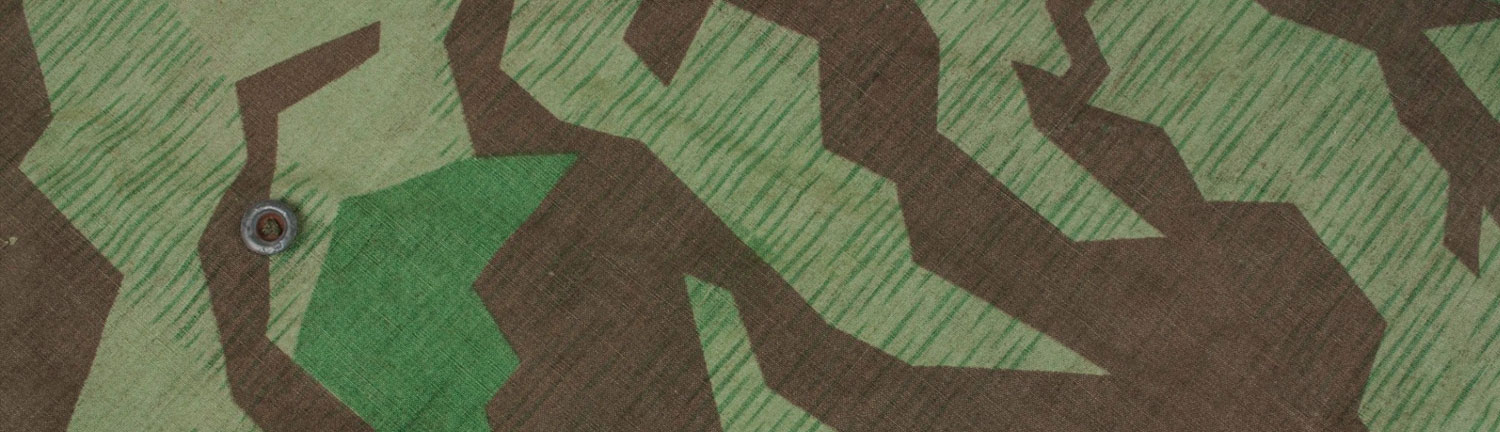

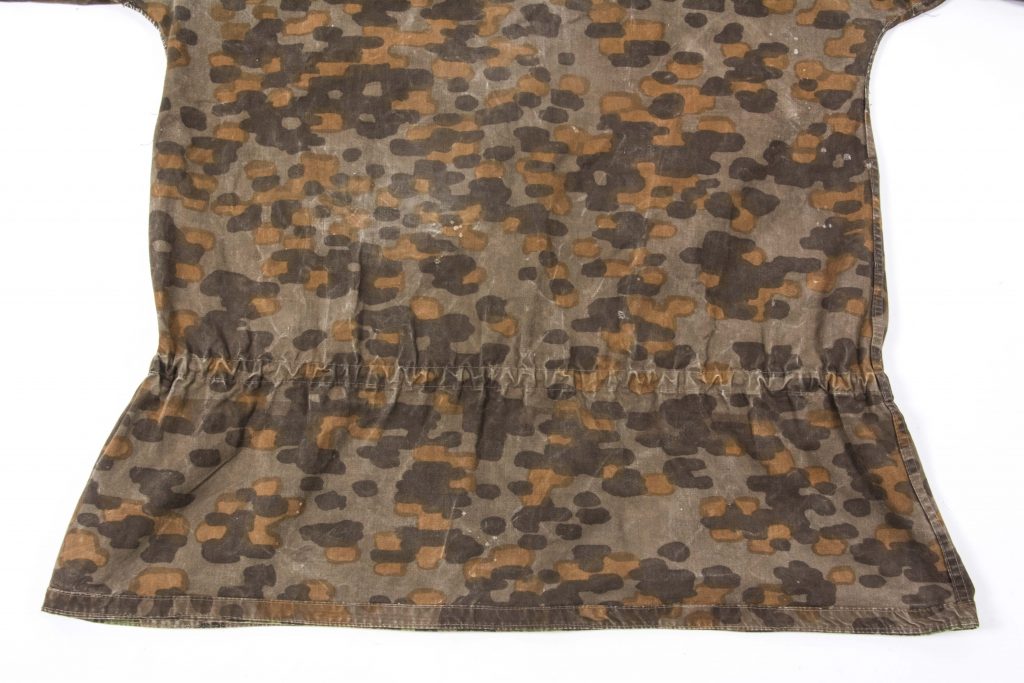

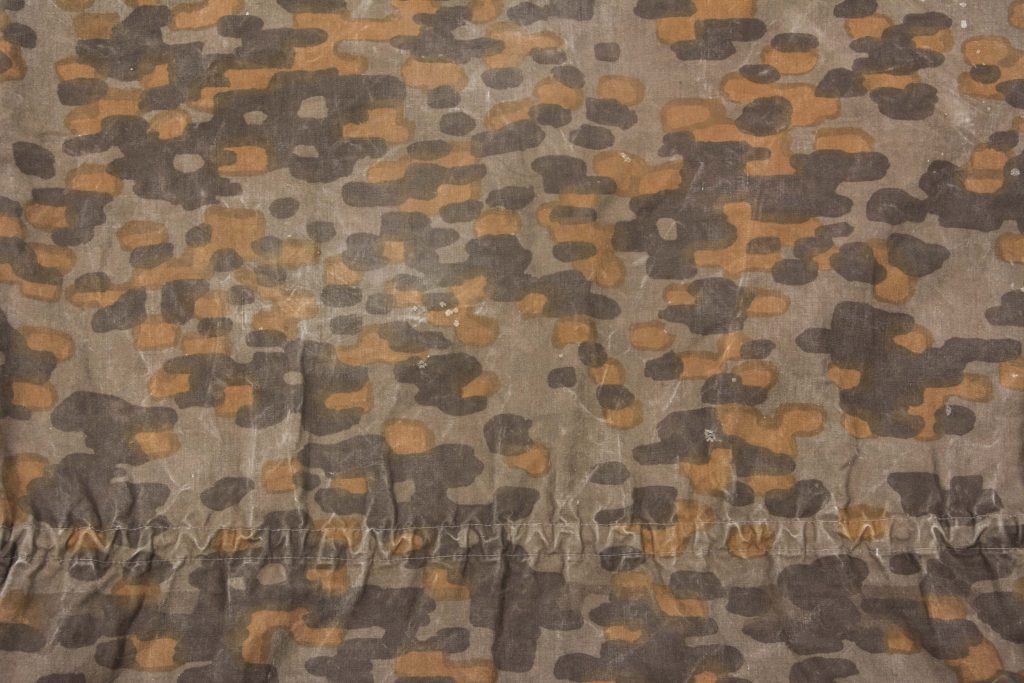

Lateral Plane Tree was the first camouflage pattern to go into mass-production. This pattern was the direct offspring of “Block” pattern and was based directly off of the same art, showing a softer, less-jagged and more filled-out appearance. Implemented in 1938, this pattern was an interpretation of the Sycamore tree’s bark and was printed via a hand-screening process using fiber-reactive dyes. Three colors made up each respective side with overlap creating further and deeper tones and colors. intended for use as smocks and helmet covers only. Because of the very short repeat (again, like Block pattern, only 32″ tall which is the height of a smock) this pattern was not intended for use as zelts. While Lateral Plane Tree smocks were, for the most part, only seen during the early campaigns in the west, as well as use in Finland, the pattern itself was actually extremely common throughout the war in the form of helmet covers and m42 caps. It is also extremely common to find this pattern being used for the head-holes on zelts right up until the end of WWII.

The beauty and rarity of this stunning smock cannot be overstated. Fewer than 30,000 1938 model smocks were produced during the war. When one considers the heavy losses incurred at this time, it’s amazing any examples remain today, It would be called “textbook” if there were known examples shown in any textbooks. To date, this is the only intact and complete lateral smock to be known to the general public. Two other examples are known to exist, one of which is is a sad state of tatters. Typical of early smocks, this was sewn using a single-needle machine. This absolutely stunning specimen exemplifies the classic model 1938 smock and is the quintessential representation of the early development and progress in SS camouflage.

What most notably sets the model 1938 smock apart from other, later variations, is the wide, elasticized collar. This was the first feature of the SS smock to be dropped.

The chest closure features facing reinforcement capped off with a rectangle placate to resist tearing at the weak point of the opening (a feature that would have been advantages on the slash pockets as well.)

Like all 1938 smocks, the fall side features a wind flap that serves to close off the opening and conceal the buttons of the wearer’s field jacket.

Another classic feature of 1938 models, the skirt hem is completed by sewing a separate strip along the hem line, rather than simply folding and hemming. This practice was carried over to some 1940 models but ultimately abandoned, most likely due to the added labor, time and material needed to yield an ultimately pointless finishing touch that could be easily achieved with a simple hem.

Like the vast majority of earlier model smocks, we see that the waist band, collar, chest closure and vertical pocket reinforcements are all sewn on the summer side of the smock. While not the 100% rule, this seems to be the most common norm on earlier smocks. As time went by, it seems the fall side was more favorable for sewing the waist band, as seen on the vast majority of 1942 models.

At the cuffs, we see even more classic features of earlier pattern smocks. The edges show how the pattern of itself extended almost completely to the selvedge of the fabric bolt. This is the result of the manner in which the cutting pattern was laid out on the printed fabric bolt. The fabric bolt itself was not wide enough to allow a seamless sleeve to extend to the wrist of the smock, this is why we see what are commonly known as “lowers.” When the pattern was laid out on the bolt, the arms reach to the selvedge of the fabric and the portions that fell below the sleeves were used to create the sleeves and cuffs, therefore they fell on the selvedge as well. This is why we typically see the numbers of numbered patterns falling on the lowers of smocks, because this is where they land on the cutting pattern. Unquestionably intentional, the cuffs and sleeve edges falling on the selvedge of the fabric eliminated the need for further hemming as the weave of the selvedge would not fray. There are some examples that show evidence of being treated with a glue as well. This is also why it was not uncommon to see raw, white fabric peaking through at the cuffs and at the edge of the smock body where it meets the lowers.

Of particular note on this smock at the cuffs is the manner in which the elasticized wrists are closed off. A rare feature of the earliest smock only, even by model 1938 standards, was that the elasticized wrists were not sewn off at the main seam, but had tiny cuts, exposing the elastic cording where it “jumps” the main seam. This smock itself features non-elastic cording, an exceptionally rare feature almost never encountered.

Another interesting feature of this smock are the armpits. We can see that they have been hand-sewn closed but it would appear that this smock initially featured factory sewn armpit vents, a feature typically only encountered on later model smocks.

The vertical chest openings show exemplify a commonly encountered flaw of smocks with this feature; tears at the weak points. The vertical cuts that make up the pocket openings, unlike the chest placket, were only “reinforced” with a few back-stitches created by sewing over the same section a few times. Needless to say, this was not sufficient to prevent vertical tearing, especially when one considers these vents were intended to be the primary access point to ammo pouches and other gear. Today, a good majority of these smocks show vertical tearing at these weak points, this smock is no exception.

But what sets this smock apart is the pattern itself. As mentioned, the rarity of this smock is beyond words. We see the body made from the easily recognizable lateral plane tree pattern. Also as mentioned, the lateral pattern was only as tall as the smock itself. Because of this, the same landmarks can easily be spotted on both the front and back of the smock itself, a feature that the larger, numbered, plane tree patterns avoided. Another drawback of the shorter artwork is that in order to avoid white lines separating where the repeat starts, an overlap is unavoidable. One can readily see where the prints overlapped during the hand-screening process along the top of the shoulders. Something we also see in the polyspot pattern and later the “unnumbered” pattern (which itself was an evolution of lateral).

Something that can be easily overlooked is that this smock features lowers, collar, waistband, pocket backing and pocket flaps made from an extremely early and significantly more rare version of the classic war-time 1/2 plane tree. What sets this version apart from the later, more common (still fully hand-screened) version of 1/2 is the cutting blocks that run diagonally from one corner of the pattern to the opposite corner. This early version has the blocks somewhat shifter from the adjoining block. This feature would not reappear until the beginning of the overprint process. Typical hand-screened 1/2 has these diagonal blocks in-line with one another, in this example we can see the shifted blocks, creating sharp stepped angles.

A true museum piece and a historical rarity, this is one of the most rare smocks to exist and we are truly beyond lucky to have the ability to examine it in such great detail.

FJM44 Collection

Photo copyright FJM44.com

Text by Chris Dillon